To some,

this notion will seem ridiculous—but to others, it will seem true beyond doubt.

Paul Watson from Sea Shepherd leans toward the latter category, and it’s quite evident he knows what he’s talking about: “Cetologists observe, document, and decipher evidence that points to a profound intelligence dwelling in the oceans. It is an intelligence that predates our own evolution as intelligent primates by millions of years.”

A few years

ago, I stumbled across an article online that was talking about the

intelligence of octopuses. I have always been fascinated by the ocean, and I’ve

spent most of my life as close to a beach as I could find myself, so this

article definitely caught my attention.

When I read

through it, and read through it again, I realized that my thinking on ocean

life had been wrong.

Octopuses

are, in fact, some of the most diversely intelligent creatures on earth, and

each of their individual tentacles has a separate “brain” that controls its

movements, colors, and reaction to the environment around it.

Not only

that, but they can display emotions, and react to human interactions in a way

that could be more intuitive than how we react to each other. I was blown away.

I had always suspected that intelligence wasn’t just “ours”, and yet I had no

idea to what sort of level other species had reached. Especially those species

who live in the great depths of the beautiful blue sea.

Captain Paul

Watson, the director and helm of Sea Shepherd Conservation Society, has been

studying the behavior and intelligence of all manner of ocean-dwellers for over

35 years, and he too is amazed by the depth, and breadth, of their aptitude.

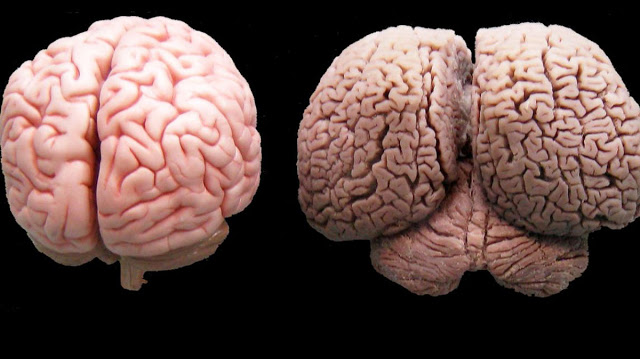

He recently

published on article on his Facebook page entitled The Cetacean Brain and

Hominid Perceptions of Cetacean Intelligence that speaks towards the call of

altering our perceptions of that which we have come to believe, and look upon

ourselves as not being the superior holder of intellect on this planet.

What is most

striking in this well-crafted article is how he calls out science itself, and

our long standing allegiance to its stance on the supremacy of man.

“Ingrained

anthropocentric attitudes dismiss the very idea that a dolphin or whale could

be as intelligent as a human being, or more.

In this

respect, science is dogmatic and intransigent, differing little in attitude

from the Papal pronouncement that the Earth could not possibly revolve around

the sun.”

Paul seems

to be calling out to our way of thinking, and asking for us to make a change.

We have stayed within the confines of the square that science has built us, and

by doing so, may have pushed ourselves way to far away from the way things

could be. Indeed, we may find, through an evaluation of self, and the way in

which we expect other creatures to be so much more lowly than ourselves, that

we have been committing atrocities that we many never have wanted to commit.

“It is an

observable fact that whales and dolphins hold a special place in the hearts of

human beings. We have had an affinity with them for years, recognizing in them

something that it has been difficult to put a finger upon. What we do know is

that they are different from other animals, apart from them in a manner that

suggests a unique quality that we can intuitively recognize. That quality is

intelligence.

Recognizing

this quality has profound moral responsibilities. How can humans continue to

slaughter creatures of an equal or superior intelligence? The path toward the

reality of inter-species communications between cetaceans and humans may lead

us to the recognition that we have been committing murder.”

Science has

been under fire as of late, and Paul isn’t the only one who has brought a cruel

spotlight on our reliance on it as a way of manipulating, and altering, a world

that may have been set up for us all to share. Rupert Sheldrake also brought up

an argument against this “dogmatic” way of going about our lives in a TED Talk

entitled The Science Delusion. Unfortunately, that talk was banned, which

raises the question of whether these men have been pushing a red-hot button

that gets under someone’s skin. If so, what does that mean for the way we think

of ourselves? And how does that play out for our future?

Watson

really has a way with his words, and his article is something to check out. The

very last quote has stuck with me these last few days, and begs me to keep

asking myself whether or not I can trust the way of thinking that has passed

down to me by scientific forefathers:

“They say

the sea is cold, but the sea contains the hottest blood of all, and the

wildest, the most urgent.” — D.H. Lawrence, Whales Weep Not

If we cannot

make the changes that we want to see in this world, than who else will?

Maybe if we

can make those changes, we then will be able to live in closer harmony with the

octopuses, dolphins, and great blue whales of this world.

Comments

Post a Comment