Humans are

in the process of herding the world's largest animals right over the brink of

extinction, and the main driving force is our insatiable appetite for meat.

It's a dire

warning, and it comes from the first analysis to look at how humans have

impacted the world's "megafauna".

Bringing

together over 300 species of unusually large vertebrates - including polar

bears, blue whales, hippos, saltwater crocodiles, ostriches - the findings

illustrate a woeful future for our shared environment.

All told, at

least 200 megafauna species are dwindling in number, and more than 150 are

being pushed under the shadow of extinction.

"Our

results suggest we're in the process of eating megafauna to extinction,"

says lead author William Ripple, an expert in ecology at Oregon State

University.

"In the

future, 70 percent will experience further population declines and 60 percent

of the species could become extinct or very rare."

If humans

choose to continue on this path, the loss could jeopardise the planet as we

know it. Biodiversity is essentially the variety of life that holds up all the

ecosystems in the world, but after millennia of unchecked actions, humans are

now facing an environmental crisis.

Imagine it

like a game of Jenga. The more pieces we remove, the more unstable the whole

system becomes, only increasing the threat of collapse.

"Maintaining

biodiversity is crucial to ecosystem structure and function, but it is

compromised by population declines and geographic range losses that have left

roughly one fifth of the world's vertebrate species threatened with

extinction," the authors write.

The problem

has been building up for a while now.

Ever since

the late Pleistocene, over a hundred thousand years ago, humans have wreaked

havoc on the world's biodiversity, sending large vertebrate after large

vertebrate into the abyss of extinction, at a rate not seen in the previous 65

million years.

But in the

past 500 years or so, things have started to speed up, and it's got scientists

worrying. Today, every single class of megafauna is most at risk from human

hunting.

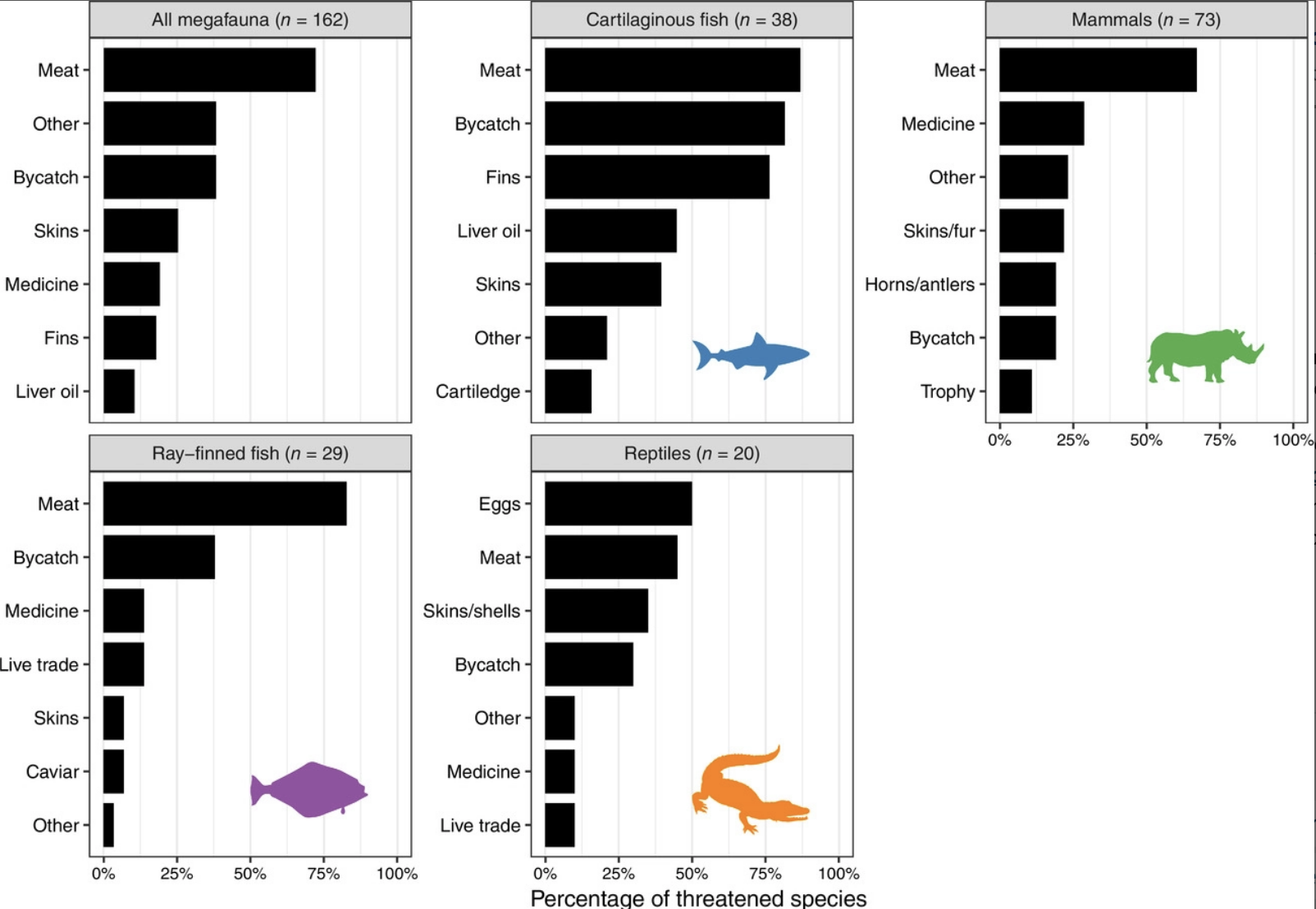

In fact, of

all the threatened megafauna species, 98 percent were at risk from "direct

harvesting for human consumption of meat or body parts."

Not only do

these large creatures hold more meat and potentially more glory, they are also

less abundant than smaller species and they reproduce much slower.

This puts

large vertebrates at exceptional risk of extinction, not just from hunting, but

also from the degradation of their habit.

"Megafauna

species are more threatened and have a higher percentage of decreasing

populations than all the rest of the vertebrate species together,"

explains Ripple.

So even

though megafauna have a small, collective biomass, their ongoing loss is

already changing the structure and function of our ecosystems, in ways that we

are still discovering.

In the past

250 years, we know that nine megafauna species have either gone extinct

completely, or gone extinct in the wild. The animals with the greatest threat

are those on land.

This is no

doubt because humans can reach them easier. For instance, in 2012, two species

of giant tortoise disappeared, and two species of deer.

Marine

creatures have it marginally better. Only 27 percent of the species are

assessed as threatened, but there are also more than two dozen that we just

don't know enough about to say.

Bony fish,

like sharks, skates and rays are at the top of the list, more at risk on

average than any other marine group.

Yet in the

end, it was those large creatures who frequent both the land and the sea that

saw the worst outcomes. Of all the mega amphibians, only one species remains on

Earth.

Weighing in

at 40 kilograms and stretching up to 1.8 metres, the Chinese Giant Salamander

(Andrias davidianus) is sometimes called a living fossil, one of the few

survivors in a family that dates back 170 million years.

Considered a

delicacy in Asia, it is now critically endangered and scientists say it is only

a matter of time before it too disappears.

Afraid that

more creatures are headed in the same way, the authors urge that "our

heightened abilities as hunters" be matched by "the sober ability to

consider, critique, and adjust our behaviors."

Otherwise,

we might end up eating the last of our planet's megafauna.

"Preserving

the remaining megafauna is going to be difficult and complicated," saysRipple.

"There

will be economic arguments against it, as well as cultural and social

obstacles. But if we don't consider, critique and adjust our behaviors, our

heightened abilities as hunters may lead us to consume much of the last of the

Earth's megafauna."

This study

has been published in Conservation Letters.

Comments

Post a Comment